Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

J Sustain Res. 2025;7(3):e250048. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20250048

1 Institute of Geography Education, University of Cologne, Cologne 50923, Germany

2 INGENIO (CSIC-UPV), Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia 46022, Spain

3 Campus Central, University of Panama, Apartado 3366, Panamá

* Correspondence: Alexandra Budke

Tourism is a major driver of economic development in Panama, but concerns about its sustainability have prompted growing attention to stakeholder engagement and governance. This paper examines the diversity of stakeholder perspectives on the sustainability impacts of tourism in Bocas del Toro, Panama. The research aims to understand how divergent views on the current and future sustainability of Bocas del Toro as a tourism destination might undermine efforts toward a more sustainable transition. The research draws on transition theory and a multiperspective approach to assess sustainability visions. We conducted a mixed-methods study combining 301 surveys and 37 in-depth interviews with four key stakeholder groups: tourists, locals, expats, and service providers. Perceptions of tourism’s economic, social, cultural, and environmental impacts were compared across groups, and qualitative content analysis was applied to identify commonalities and divergences. Results show that while economic benefits are widely acknowledged, disagreements over environmental, social and cultural impacts persist. Environmental degradation and climate-related risks were under-recognized or deflected by most stakeholders. A shared vision for sustainability was largely absent, and perceptions of responsibility were fragmented. Trust in governance was low, and mechanisms for stakeholder collaboration were weak or nonexistent. The lack of ashared vision, limited stakeholder collaboration, and unequal attribution of present serious challenges to steering sustainability transformations in Bocas. These findings underscore the need for greater collaboration and dialogue among stakeholders to co-create a collective vision, improve ecological awareness, and diversity business to guide the region toward a more sustainable future.

Tourism in Panama is one of the country's most important economic sectors and, except for the pandemic years, it has experienced very strong growth over recent years. In 2022, the number of international visitors exceeded 2.5 million, a number higher than the pre-pandemic period and the latest data show that from January to June 2024 there was an increase of 8.7% of international visitors as compared to the same period in 2023. In fact, the country received in the same period a foreign exchange income of $3083 million in 2024 as compared to $2795.6 million in 2023 [1]. For a country with a population of 4.4 million, the volume of tourists is considered high. ATP reported that economically, tourism represents about 11% of the GDP and generates USD 5 billion of foreign exchange. It is estimated that the sector generates 40,000 direct jobs and 100,000 indirect jobs [1].

Located on the Caribbean coast, Bocas del Toro is one of Panama's most important tourist destinations. The archipelago is promoted as a collection of small paradise islands, idyllic nature, tropical rainforest, palm-fringed sandy beaches, coral reefs and Caribbean flair [2]. The destination has gained in popularity over the last years leading to profound economic, social and cultural transformation. Currently, the destination challenge is to find pathways that can contribute to poverty reduction and empowerment of the population, without destroying the paradisiacal nature that is the basis of tourism activity [3]. Such pathways need to incorporate solutions that help mitigate and adapt to climate change [4] while avoiding negative effects of overtourism [5,6], and, include communities in the decision-making process and the protection of natural resources [7].

In this context, the National Tourism Authority (ATP) launched in 2020 the Master plan for Sustainable Tourism in Panama, which includes Bocas del Toro as a key destination. According to the plan, the future vision for Bocas del Toro is to turn the archipelago into an ecotourism destination, focused on multi-activity, especially related to the marine environment, including local culture and traditions, wildlife observation, and nautical activities. In terms of natural heritage, the various islands of the archipelago host a vast biodiversity of marine and terrestrial life, with over 200 species of tropical fish, more than 400 bird species, 28 different amphibians, 4 types of sea turtles, 3 kinds of monkeys, unique dolphins, manatees, and 3 species of sloths [8]. However, this natural heritage is at risk: dolphin populations in Dolphin Bay are dwindling, and coral reefs are negatively impacted by water pollution [8]. Therefore, combining tourism with conservation is not only desirable but a priority for the sustainability of tourism in the destination. According to ATP, there is also potential for developing community-based tourism, as envisioned in the Master Plan. Several communities are open to engaging with visitors and sharing their lifestyles. Additionally, the region's rich history (pirates, treasures, Spanish passage, and even an indigenous king) could enrich and differentiate the tourism offering from its competitors.

Achieving such transformation requires sustainable actions by all tourism stakeholders. This is only possible if unsustainable practices in tourism and their negative consequences in the different dimensions of sustainability (ecology, economy, social, culture, and infrastructure) are recognised by stakeholders, if they are attributed to tourism, and if consequences for their sustainable actions in the future are derived. Hitherto, existing literature has been limited to analysis of structural data on the economy or the ecosystem [9], ignoring almost completely the visions of all the actors and the extent to which they align with the visions of transformation set up by the tourism authorities of the country. Adopting such a perspective, allows us to address the following research questions:

i.

ii.

iii.

Our analysis focuses on the perspectives of the main stakeholders in tourism development in Bocas del Toro (tourists, locals, expats, tourism entrepreneurs, and government agencies). Data was collected through 439 surveys and 25 in-depth interviews with all actors. By comparing the different points of view, the different objectives of tourism development, and the perceptions of (non-)sustainable tourism development, similarities, differences, and contradictions can be visualized, which can explain the actions of the actors. After presenting the state of research, the micro-analytical, multi-perspective methodological approach is described, and the extensive data is analysed. This is followed by a presentation of the findings in relation to the research questions. The views of the groups interviewed are then compared and discussed. In addition, opportunities for actual sustainable tourism development in the sense of the Panamanian Tourism Authority (see above) are derived.

Over the past decade, academic and non-academic literature on sustainability transformations has surged [10]. Since the Brundtland Report (1987), sustainability has been a key principle for global development, encompassing economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Although these dimensions are seen as complementary, their relative importance remains debated [11]. Social sustainability, in particular, is often considered less developed and is usually framed in relation to ecological or economic aspects [12].

Sustainability science emphasizes ensuring human well-being while safeguarding Earth’s systems [13]. This “strong sustainability” perspective advocates for a balance that supports social and economic well-being within planetary boundaries [14,15]. It shifts the focus from reducing environmental impacts to fostering systemic change through radical social, institutional, and economic innovations [16]. Such transformations require "advanced and comprehensive approaches" for understanding and governing sustainability transitions [17].

In recent decades, a variety of sustainable tourism models such as ecotourism, nature tourism, responsible tourism, and regenerative tourism have proliferated, each contributing uniquely to the sector's sustainability [18,19]. Transformation in this context means pursuing a specific aim, with the definition of this sustainable goal having profound implications for stakeholders, sectors, and the various dimensions of sustainability in policy formation and execution.

Environmentally sustainable tourism is most closely associated with ecotourism and nature tourism. While nature tourism is primarily focused on the tourist's experience of nature and wildlife, typically in protected areas, ecotourism is distinguished by a commitment to practices that benefit both natural resource conservation and local communities. The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) defines ecotourism as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local communities.” [20]. This form of tourism often combines nature tourism with small-scale accommodations and a widespread acknowledgment of environmental value by tourism professionals, prioritizing environmental considerations, followed by social and economic factors [19].

Despite the emphasis on the environmental dimension, sustainable tourism requires a comprehensive approach addressing social, cultural, economic, environmental, and managerial dimensions. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) conceptualizes sustainable tourism as encompassing both current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts, meeting the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities [21]. Cultural sustainability encompasses respecting the sociocultural authenticity of host communities and conserving their cultural heritage and traditional values, as well as managing the impact of tourist visits on cultural sites. Social sustainability addresses both the positive and negative effects of tourism on the social well-being of communities, including community support, preventing exploitation and discrimination, safeguarding safety and property rights, and contributing to local poverty alleviation. Economic sustainability is about ensuring long-term, viable operations that provide equitable socio-economic benefits, such as stable employment and income opportunities. In addition to the socio-cultural and environmental dimensions of sustainability, the Global Sustainable Tourism Council [20] emphasizes management capacity as essential for enhancing tourism sustainability, including the judicious use of natural resources, the maintenance or improvement of key ecological processes, the conservation or regeneration of natural resources and biodiversity and, generally, the capacity to govern a transition towards a sustainable future.

Governing sustainability transitions involves steering change toward desired outcomes. Transformative processes include experimentation, capacity building, and co-creation of knowledge and visions [10,22]. In co-creating visions, sustainable tourism requires a multiperspective approach that allows to take into consideration perceptions and opinions of actors. Any plan for sustainable development must involve stakeholders’ perspectives since they are key actors in achieving the goals of these plans [23]. This needs to be done in an inclusive way where what they called the interest groups must be represented having an active participation in the decision-making process, instead of working individually [24]. Furthermore, engaging stakeholders values and emotions are key for lasting sustainability impacts [24].

However, achieving a high degree of participation in the co-creation process is far from automatic. Community trust, place attachment, and quality of life are critical mediators in sustainability pathways [25,26]. These three social and psychological dimensions help explain stakeholder buy-in and vision alignment, which are crucial to co-created transformation processes [27]. Furthermore, community trust, place attachment, and quality of life have the potential to bring together diverse stakeholders who collaborate, build strong social networks between governments, and draw on multiple knowledge sources to create collective visions for a sustainable future. However, we know very little about the diversity of visions around transformations, particularly how different stakeholders perceive the impact of certain activities, like tourism, on sustainability.

Sustainable Tourism in Latin AmericaTourism studies in Latin America have shifted significantly. Echeverri and Viera [28] note that while earlier literature focused on conceptual models and trends, recent research increasingly emphasizes sustainability [29] and green tourism [30]. Challenges to achieving sustainable tourism in Latin America include rising traffic, high prices, and waste in Guanajuato, Mexico [31], vulnerability of community based tourism in coastal areas due to climate change in the Caribbean [32], lack of awareness among main actors involved in tourism activities to achieve sustainable development [33]; lack of sustainable development awareness in early-stage tourism areas like Córdoba, Argentina [27], and procedural justice issues among Maya residents in Quintana Roo, Mexico [34]. There is a controversial debate in the scientific community as to whether tourism can contribute to reducing poverty and thus social sustainability [35]. Data is available for Latin America that suggests this connection [36].

Management capacity is essential for sustainable tourism, requiring coordinated planning with local stakeholders [37]. Peralta [38] identifies ten pillars for sustainable tourism recovery in Central America, emphasizing community involvement, cultural and natural heritage conservation, sustainable business practices, and climate resilience. Sustainable tourism transformations require organizational changes, such as shifting to local supply chains, developing new products, and assessing impacts on the environment, society, and economy [39].

Creating unique tourism experiences involves integrating natural and cultural elements while fostering meaningful connections between tourists and local communities. Community tourism is one of the ways to promote this sustainable development [24].

Additionally, environmentally sustainable tourism requires managing natural resources, mitigating negative impacts, and contributing to ecosystem restoration. Latin American countries must develop responsible tourism practices that respect the environment and empower local communities [40,41].

Existing studies emphasize that innovative governance models for sustainable tourism should be inclusive, multi-scalar, and involve co-created plans and transparent stakeholder communication. Reliable data is essential for monitoring and improving sustainability initiatives.

In terms of geographic coverage, the majority of studies on sustainable tourism in Latin America and the Caribbean come from countries such as Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Argentina, while most of the other countries are neglected [28]. In this sense, this study seeks to add information on sustainable tourism focusing on Isla Colon in Bocas del Toro, in Panamá, a small but very active area that mainly depends on tourism.

In conclusion, transitioning to sustainable tourism in Latin America requires integrating social, economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions, with a strong focus on community development and stakeholder perspectives. Governing such transition requires the co-creation of visions around the desired sustainable future. However, current studies on sustainability transformations in tourism tend to be based on data collected from just one or two stakeholders, ignoring the diversity of visions from different communities of actors interacting in the destination. This paper addresses this gap by examining the divergent views on the current and future sustainability of Bocas del Toro as a tourism destination.

The main attraction of Bocas del Toro (see Figure 1) is its beaches, featuring turquoise waters and unique ecosystems in the Caribbean Sea. The typical tourist profile in Bocas del Toro is predominantly international. According to data from the ATP (Panama Tourism Authority), a significant percentage of visitors come from the United States, Canada, and European markets such as Spain, Germany, or the United Kingdom, accessing the area by plane, with small-capacity aircraft, or by road. Due to its proximity to Costa Rica, there is also a substantial number of visitors from Costa Rica entering by road. The presence of national tourists is limited.

The predominant type of tourism in Bocas del Toro is “sun and beach” tourism [42]. However, the destination also offers (though not yet fully developed) possibilities for other types of tourism, such as adventure tourism related to water sports, cultural, ecological, or scientific tourism. Indeed, the tourist profile visiting Bocas del Toro is quite diverse, including ecotourists seeking intense contact with nature and the marine ecosystems of the area, and backpackers looking for sun, beach, and party experience.

Despite its rich natural and cultural resources, Bocas del Toro faces serious deficiencies related to (a) infrastructure overload and (b) low levels of basic services due to limited physical space, exacerbated by (c) the lack of territorial planning. Infrastructure limitations include the severe deterioration of Bocas del Toro Airport, lacking basic services for tourist comfort, and a single-lane road in each direction requiring 9 to 10 hours of travel from the capital (4–6 from neighboring Costa Rica). Transportation between islands is by boat. According to ATP data, there are currently between 1500 and 2500 transport operators with varying degrees of formality, complicating the implementation of sustainable tourism strategies. The Master Plan highlights the need to address environmental malpractices—repetitive routes, harassment of marine fauna, concentration of many boats in few spaces, noise, waste, etc.

Among basic service deficiencies, notable are limited access to potable water, poor solid waste management. Only 50% of Bocas del Toro's population has access to potable water, and 6% to sewage systems [8]. The situation is considered very serious regarding basic infrastructure like electricity, water, waste management, and transport maintenance. Despite the current deficiencies, ATP believes that Bocas del Toro has significant potential for development as a priority sustainable tourism destination in Panama, particularly to develop ecotourism aimed at tourists interested in conserving natural and cultural heritage.

Research DesignA mixed methods approach [35] was used to gather the perceptions of key stakeholders in tourism development in Bocas del Toro, using both qualitative and quantitative surveys and in-depth interviews. The surveys to tourists, touristic establishments, and residents were conducted in the field in the spring of 2023 as part of two different but complementary projects. The first one was funded by UN-ECLAC on sustainability gaps in tourism destinations in Panamá [43]. The second one was a cooperation project on tourism with students from Cologne university in Germany the Universidad de Panamá. Additionally, in-depth interviews were conducted with a selection of experts and organizations, including the chamber of tourism, the chamber of industry or the local and regional administration, etc.

Tenor [7] emphasizes the need to have different perspectives from tourist entrepreneurs to community members and leaders and other stakeholders that will enrich the research. She also mentions the use of data collection interviews from key stakeholders from the tourism sector. This diverse range of opinions contribute to a better understanding of how stakeholders perceive sustainable tourism.

Sample and Data CollectionFor data collection, the sample size for each survey was estimated with a confidence interval of 95% and 90% [44,45]. Ensuring a sufficient sample size allows for the extrapolation of results to the entire population of individuals and organizations at the destination, thereby providing statistical validity. However, this also requires a greater effort in data collection. Our calculation shows a high representativeness of the sample (see Table 1). One of the limitations encountered when estimating the sample is that some of the available data on the target population is at the regional level, rather than at the destination level. The population at the destination (whether residents or tourism establishments) is likely to be smaller than the population at the provincial level, which is the basis for some of the available data. Typically, a smaller population requires a larger sample size. Therefore, the following data should be interpreted with caution and considered as indicative.

Data was collected through a face-to-face survey and interviews. The surveys and interviews were conducted in the spring of 2023, both on Isla Colon, the main island of Bocas, and in Bastimento and San Cristobal by a large number of trained interviewers in public spaces and by personnel from the Regional tourism authority. The interviews with tourists and residents were conducted in English, German, or Spanish, depending on the interviewee. The survey to service providers and residents was in Spanish. A guideline was used to make the results comparable.

For the tourists and the interviews with residents, the audio recordings were transcribed using Sonix software (SONIX, USA), and the transcriptions were then checked and corrected by project staff. The open-ended questions were recorded using ArcGIS Survey123 (ESRI, USA). The survey on accommodation and other touristic activities collected data on the social, environmental, cultural, and economic sustainability of their activities, as well as their management capacity. In what follows, we describe how data was collected from each stakeholder group.

ResidentsData was collected using two different methods: a closed short survey, which enquired about the perceived positive and negative impact of tourism on the community using a Likert scale, which followed the WTO guidelines; and an open questionnaire which enquired about the perception of Bocas del Toro, the evaluation of tourism and the future development of tourism. The short, closed questionnaire was applied to 57 residents of both Colón and Bastimento. Qualitative interviews with open questions were conducted with an additional 67 residents of Isla Colón (57 Panamanian nationality and 10 Expats).

Among the Panamanian locals were 14 women and 43 men. The interviewees belonged to different age groups, ranging from 18 to over 70 years old. The reported household income is much lower than that of the tourists. 36% said they had less than $500 per month, 34% had between $500 and $999, 23% had between $1000 and $2999, and 7% had over $3000. The level of education of local Panamanians surveyed is also much lower than that of tourists, with only 14% having a university degree.

Additionally, 10 Expats from eight different countries of origin (6 men and 4 women) of different ages were interviewed. 50% reported a household income of less than $3000 per month, and 50% had between $3000 and $7999. 66% had a university degree.

TouristsQualitative interviews with open questions were conducted with 239 tourists (117 men and 122 women). These were people who had been on Isla Colon for less than a year. 46% of the tourists were under 30 years old, 43% were between 30 and 60 years old, and 11% were over 60 years old. The respondents came from 79 different countries of origin. The main countries of origin were Germany (23%), the USA (14%), Canada (10%), and the Netherlands (9%). Reported household incomes varied considerably. 31% reported a family income of less than $3000 per month, 42% had between $3000 and $5999 per month, and 27% had more than $6000 per month. Depending on their income, respondents spent different amounts of money per day, while 51% spent a maximum of $51 per day in Bocas, 49% spent much more. The maximum reported was 700 euros per day. The respondents' level of education was mostly high, with 77% having a university degree.

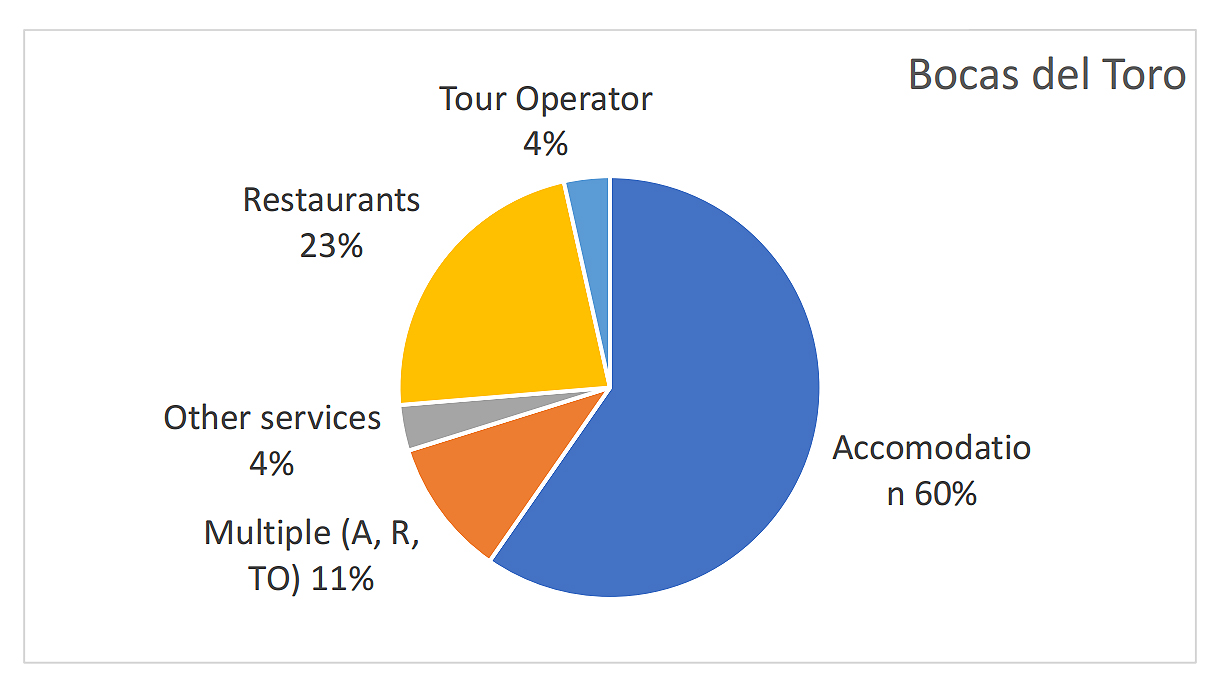

Tourism ProvidersUsing a closed questionnaire, information was collected from tourist organizations. A distinction was made between accommodations and other organizations that offer other tourist activities, such as restaurants or tour operators. In total, 56 questionnaires were completed. The survey was done in person. Figure 2 shows the distribution per type of service provided. The totality of the service providers are SMEs, with 84% being micro-enterprises [44].

Figure 2. Distribution of tourism providers by type 2023. (Source: Chaminade (2023a) [45].)

Figure 2. Distribution of tourism providers by type 2023. (Source: Chaminade (2023a) [45].)

The open-ended interviews were analyzed through content analysis using MAXQDA [46]. The deductive development of the overarching categories was based on the sustainability dimensions (environmental, economic, social, and cultural) often described in the literature [47] when coding the ‘assessments of the impact of tourism’ (see Table 2). As we wanted to find out whether respondents attribute changes in their environment to tourism at all, the category ‘Perception of Bocas’ was formed with positive and negative judgements (see Table 1). The category ‘Visions of the future’ was created to see to what extent sustainability considerations play a role in this context. The text passages were coded according to the categories (see Table 2). A communicative validation of the coding was carried out. The coding was checked by another rater. The Cohen’s Kappa was 99%, so that the interrater reliability can be regarded as very good. The analyses were first carried out separately for the four survey groups in the sample, and the results were then summarised and compared in a table.

The 62 indicators collected via a closed survey (to tourism service providers and residents) were analyzed individually and in aggregate form. The individual indicators are directly derived from survey data and constructed using Excel pivot tables. Although precise, they are not easily comparable, limiting their ability to highlight gaps or trends. To address this, the indicators were transformed into a comparable scale, allowing for aggregation [44]. The scale ranges from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates “non-compliance,” 1 “insufficient performance” (progress but not systemic), 2 “improvable performance” (systemic progress but no planning), 3 “good performance” (planning in place), and 4 “excellent performance.” This transformation introduces subjectivity, although it makes the results suitable for visual communication and allows for comparability and aggregation across dimensions [44].

The multi-perspective views of the groups interviewed are presented below in relation to the research questions formulated at the outset.

Perceptions on the Transformation Process and the Role of TourismTourists' perceptions of Bocas del Toro relate exclusively to tourism, as most respondents are visiting Bocas del Toro for the first time and do not compare their current perceptions with previous ones. Their evidence of change comes mainly from the construction sites they observe; the renovation of older buildings is also perceived and valued positively.

“I think everywhere it changes the place for the better. I mean, there’s stuff that’s under construction, and there’s the renovation building. So I think it’s improving. It’s the older buildings. They look pretty shitty. But the ones that have been rebuilt, they look nicer.” T306.

In the tourists’ statements, there are 34 negative, 22 neutral, and 224 positive assessments of the place. The respondents generally base their judgment on their experiences in other tourist destinations and compare them with Bocas. They also compare their expectations with the reality they found. A large proportion of respondents rate Bocas very positively and compare it to paradise. These respondents see their expectations fulfilled, rate the intensity of tourism positively, and would recommend a visit to friends. The relaxed atmosphere, the beautiful beaches, and the possibility of travelling to other islands by water taxi were mentioned positively. The place is considered particularly suitable for backpackers. “Because it’s amazing! It’s paradise!” T258.

Surfers were particularly positive about the waves. The fact that there is tourist infrastructure and facilities on the one hand and a lot of nature on the other is seen as positive. This group also frequently mentions that they feel welcome by the locals and that the contact with other tourists is also very positive. “Everything is very nice here. Compared to Germany, it’s warm, sunny, and the people are nice.” T434. On the other hand, people who gave negative ratings often found that their expectations were not met. The weather is often mentioned in this context, with many expecting sunshine and blue skies and being surprised by the frequent rain. The high prices are also seen as particularly negative. “It’s like I've been to other tropical places that are cheaper and more interesting than here.” T264.

It's often said that the tourist services don’t match the price, that the accommodation and restaurants are often of low quality, and that the quality of service is poor. The rubbish in the city center and on the beaches is also often criticised. The locals are seen as responsible:

“I think they need to clean it up a bit. You know, it’s all they have. It’s all they have. So they should take care of it a little bit better, and I think that people’s first impression is that it is a little bit run down and dirty, but that is the Caribbean.” T277.

Some respondents also do not feel safe in Bocas. The perception of the intensity of tourism also plays an important role in the judgment of the place. People who consider the intensity to be too high see a loss of authenticity, feel disturbed by the noise of the parties, and judge the place predominantly negatively.

Expats’ perceptions of Bocas are also overwhelmingly positive. Above all, the beautiful nature, the sea, the beach, the tranquility, and the wildlife are described as important elements of Bocas. The interviewees feel 'at home' and see Bocas as a paradise, a safe place, and an interesting tourist destination where they can have many international contacts. They compare their lives in Bocas to their lives in their home countries, mentioning that it is cheaper, quieter, safer, and closer to nature.

“I think it’s amazing. This is amazing to live in. In Israel, it’s very hard. Like you see in the news, it’s different. And here it’s beautiful and it’s lovely.” E54.

“The good thing is that we are in the middle of nature. There’s no noise. It’s very quiet. That’s what I like very much.” E50 The expats particularly admire the nature and the sea.

In many ways, the perceptions of the locals coincide with the perceptions of the other groups. Bocas is often compared to Panama City or other Panamanian cities, and it is noted that Bocas is a quiet place with less traffic. The tranquility and relaxation are mentioned positively by many respondents.

“Well, in Panama City what I don’t like is the traffic. Here I can walk everywhere, it’s a ‘relaxed’ place.” 140.

The beaches and nature are also often mentioned in a positive light.

“Well, what Isla Colon is, what nature is, the sea, the fishing. I like all that. Swimming” E157.

The interviewees reported good neighborly relations. Neighbors help each other and feel safe. In contrast to the other groups, however, the locals perceive a profound transformation process, which they derive mainly from their memories of the former state of the place. In particular, they describe a very positive transformation from a poor fishing village to a tourist destination with many more income opportunities:

“In Isla Colon in 1991, we were dedicated to fishing, but really, everything here on the island of Bocas del Toro was dedicated to fishing. Then I went into tourism in the year 2000, I think in the year 2000 tourism came in, and well, now we are all dedicated to tourism.” E1.

But locals also report a range of problems they perceive in Bocas, such as waste, poor transport infrastructure, sewage problems, and poor-quality drinking water.

“It’s a place where you can see a lot of sewage that can affect the children later, not later, but also because it’s a place where we have no place to live. So also because of the sewage, and we also have problems with the water supply, the real truth is that there is no water here, we have no water here.” E164.

They report very high costs of living and are considering moving to cheaper parts of the country.

“I think a lot of people that, locals that live here, they’ve moved because everything, everything is more expensive, and they’ve gone to live in the Pacific, in Panama, in the city, because everything is already too expensive here.” E109.

Local people are aware of many changes in Bocas in recent years and perceive a profound transformation. They see nature being damaged and disappearing. However, this is not attributed to tourism, but to corrupt politicians.

“The worst. They have taken away the nature, the beauty of this area. But it’s not the foreigners, it’s the corrupt, the representatives, governors, mayors, and deputies.” E124.

The image of the government is often very negative. It is also criticized for not cleaning the beaches and destroying nature. It is often acknowledged that prices and expenses have risen, but this is not attributed to tourism, but often to the Chinese who own the shops and raise prices to increase their profits. The state is also accused of taxing too much. The state relocates poor people from a slum area inland in the context of the airport expansion.

Impact of Tourism on SustainabilityThe statements made by interviewees attempting to assess the impact of tourism on Bocas de Toro can be categorized into the dimensions of sustainability: infrastructure, culture, ecology, and economy. Table 3 summarizes the main findings.

TouristsTourists’ statements in the qualitative interviews (total 211) refer to the economic impact of tourism, 64 to the infrastructural impact, 54 to the ecological impact, and 35 to the cultural impact. This quantitative distribution shows that the main focus for tourists is on the economic impacts of tourism.

While the economic and infrastructural impacts of tourism are almost exclusively assessed as positive, there is disagreement on the assessment of the cultural impacts, and the environmental impacts of tourism are almost exclusively perceived as negative.

Economic ImpactsThe economic impacts of tourism are perceived to be mainly positive. They perceive a wide range of tourist services such as accommodation, restaurants/cafés, and tour operators. They see tourism as a central economic sector in Bocas del Toro.

“Well, it's Bocas. Tourism is everything, you know, 100% tourism. Nobody survives down there without tourists.” T358.

From the large number of perceived tourists, respondents often conclude that the high demand leads to more tourism businesses being set up and money being made.

“I think a lot of what’s happening is that more people are starting businesses like restaurants or travel agencies because there are so many tourists and there are opportunities.” T270.

Many of the interviewees assume and observe that tourism provides many jobs for local people and that this generates income for them. Many respondents believe that tourism brings prosperity, a higher standard of living, and satisfaction to the local people.

In addition to income and jobs, it is also assumed that local people are empowered. Only one respondent perceived that many expats have invested in the tourism business alongside locals and benefit from the income. The only negative economic impact mentioned by many respondents is the high prices, but only one person believes that the high prices due to tourism could have a negative impact not only on tourists but also on locals:

Infrastructural ImpactsTourists also mentioned the impact of tourism on infrastructure. In particular, the development of tourist infrastructure such as hotels/hostels, restaurants, cafes, tourist centers, etc. is mentioned. The road infrastructure, on the other hand, is mainly seen as poor.

“There is a lack of infrastructure here. So, yes, things like rubbish or roads or utilities” T337.

Respondents expect to see improvements in this area, in particular in the future as a result of tourism.

Cultural ImpactsThe tourists interviewed also see cultural effects of tourism. These are often described as Americanisation or westernisation.

“And I think when you come here, you get the feeling that it’s a bit Americanised. In other words, it has been adapted a little bit from Western countries.” T329.

As the examples show, tourists judge the cultural impact of tourism primarily based on what is on offer to tourists, such as restaurants or cafés, the type of new buildings, and what they perceive as the dominant presence of American and European tourists. Some tourists feel that they cannot have an authentic cultural experience during their stay.

“You’re going to visit a new culture and you don’t want them to adapt to the culture of the tourists because then it’s not so interesting to travel.” T329.

Some interviewees suspect that Panamanian culture is being lost through tourism. Interviewees very often compare Bocas with other tourist destinations and, on this basis, assess the low authenticity of the place.

“We’ve been to other places. And that’s almost party tourism, isn’t it? So I think the old charm has been lost a little bit.” T367.

A large number of respondents find Bocas too touristy and criticize the lack of contact with locals and the lack of visibility (buildings, food) of local culture and its limited accessibility. Non-American tourists, in particular criticize the high presence of Americans and the American character of the place. This is not always seen as critical, especially by American tourists. Some tourists see the Western/American influence of tourism in a positive light and assume that a cultural change towards sustainability, cleanliness, and environmental protection can begin.

Ecological ImpactsTourists often assume that local tourism has a negative impact on the environment. In some cases, there is talk of a general negative impact on ‘nature or the environment’, although it is clear from the wording that respondents are making assumptions, have made limited observations on these aspects, and have limited knowledge to draw on.

“Maybe there’s an environmental impact.” T265.

To assess the environmental impact, respondents often draw on their general knowledge of environmental damage caused by tourism. Many have noticed that the city is very dirty and that there is a lot of rubbish. Some of the interviewees put the blame for the perceived litter, which is often equated with pollution, on the local tourism operators:

“When we went to the beach there was a lot of like plastic bottles” T304.

“They should do more. They should be more, more inclined to preserve their environment and clean it up” T390.

Very few tourists associate the problems with tourist behavior and consumption. In some cases, tourists are seen as environmentally conscious and it is assumed that their behavior does not have a negative impact on the environment.

ExpatsExpats also perceive mainly positive economic effects of tourism. The social and cultural effects are also seen as positive, but the environmental effects are not mentioned.

Economic ImpactsSome expats report that they are economically dependent on tourism. The fact that it is possible to earn good money is seen as positive. The seasonality of tourism is seen as negative. Other economic effects are seen in the development of the construction sector through tourism and in the creation of sources of income. To que question: “In your opinion, how has the presence of tourists affected your neighbourhood?” the expats indicate

“For the better, because we earn good money.” E46.

It is reported that the expats also provide jobs for the local people, for example in repair work or as gardeners.

“So it gives more business opportunities. We, the people across the road, we’ve had them build fences for us, gates for us, get a permit for trees, cut down our worker who comes and does the grass with a machete and a weed eater and digs holes for plants. He’s a local, okay”. E53

Social ImpactsIn particular, international migration to Bocas is perceived positively. Bocas is seen as a place with many international influences. Tourism can lead to new friendships.

LocalsIn the qualitative interviews, the local residents perceive various impacts of tourism. The economic impacts are also very dominant in this group (72 statements) and are almost exclusively assessed as very positive, as are the infrastructural (15 statements) and cultural (12 statements) impacts. In the area of social impacts (24 statements), on the other hand, there is a predominance of critical comments, mainly related to a perceived process of spatial displacement. Ecological impacts of tourism are hardly recognized at all (3 statements).

Economic ImpactsThe economic impacts are almost exclusively assessed as very positive.

The interviewees primarily see the creation of jobs and income opportunities through tourism. “All the people work only for tourism”. L3

The fact that tourism is the most important economic activity on the island is seen as such by many, and the dependence on tourism as a source of work and income is widely shared and seen as positive. The experience of the pandemic in particular, when hardly any tourists came, showed many people how important tourism is as a source of income for Bocas:

Compared to the past (before the development of tourism), the current economic situation is often seen as much better. It is often said that the income from tourism enables people to support themselves and their families. They also refer to the tours, the shops, the hotels, the restaurants, the souvenirs, the boat transport, and the construction industry, which only provides jobs.

“With this tourism boom, things have improved. So there is land. There are lots of foreigners, there are resorts, there are hotels, there is work, there is work.” L4.

Infrastructural ImpactsMany people mention the high level of construction activity, which they attribute to houses and hotels being built and roads being improved as part of tourism development. These infrastructure measures are also seen as positive.

“There has been improvement. Yes, there’s been an improvement in the roads. Before, the roads were made of stone, dirt, uh-huh, dirt. Now they have changed it and there is supposed to be a project that will fix it better.” L141.

Cultural ImpactsThe cultural changes brought about by tourism are also overwhelmingly positive. They report that culture, clothing and foreign language skills have improved. Many respondents say that tourists bring new people to Bocas. Some report new friendships and also new skills such as speaking a foreign language as a result of contact. Tourism creates new contacts between locals and tourists, leading to permanent partnerships and the formation of families.

The contact between tourists and locals is almost always described as positive and enriching.

Many interviewees emphasise the cultural openness of the inhabitants and their multicultural roots, which predate the arrival of tourism.

“This place is like the country. A melting pot. And on this island, what is Boca del Toro, there are the Ngöbes, the Teribes, the Bogota and the blacks. And the cultures in us is a beauty.” L43.

Many interviewees said they were interested in the tourists, saw the contacts as positive and were in favor of opportunities for exchange. A few also see negative effects and think that the place is becoming too international and that the local culture is being lost.

Social ImpactsRespondents also address some of the social impacts of tourism, including living with expatriates who have often invested in tourism and are usually identified as tourists. It is in this context that most of the negative impacts are addressed. These mainly concern a process of social and economic displacement. One of the issues raised is that local people are increasingly denied access to the beaches.

“Before you could go to any beach and now when they buy or live in a place in the water area or in the sea area. They, they forbid people to go there or to bathe there.” L12.

It is also mentioned that tourism would also increase crime and drug use. Another negative aspect is that foreign investors have bought up land and the local population has sold up and moved away. A process of displacement is described.

“There’s no more land for the locals, there’s no more privileges for the locals.” L147.

“A lot of tourists come here to buy, they come here to buy and take possession of the territory, which is not really the best thing to do.” L144.

Other interviewees, on the other hand, do not perceive any social impact of tourism and speak of very stable and intact neighbourhood relations.

Ecological ImpactsThe environmental impact of tourism is rarely mentioned. Only three passages refer to it. It is reported that more environmentally conscious behaviour is spread among the locals as a result of tourists.

“Well, positive. Well, some people have practically come to teach us what recycling is, and sometimes it’s embarrassing. But if it’s true, it’s to keep our nature clean. A lot of them come and teach us, talk to us and give us an example of how to recycle”. L11.

When environmental problems are attributed to tourism, it is mainly because of the rubbish that is seen lying around: “Look at all this, garbage man. That’s what the foreigners did”. L12.

Tourist Service ProvidersThe data collected from the service providers reveals that Bocas del Toro faces significant sustainability gaps in tourism across multiple dimensions [43]. The most severe deficiencies are observed in areas such as management capacity, sustainability training—closely linked to management capacity—cultural and natural heritage protection, and the management of energy, water, and waste [44].

Economic ImpactsThe economic impact of tourism in Bocas is perceived as very strong [45]. The local economy is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with deep local roots. Although some owners are foreign, most reside permanently in the region, as do the majority of employees. A significant proportion of workers also hold permanent contracts, highlighting tourism as an important source of employment. Given the archipelago’s geography, the low level of local supply chains is unsurprising, as most inputs are not produced on the islands. The most critical issue, however, is the severely limited access to financial resources (both public and private), which constrains efforts to address sustainability gaps. This challenge is particularly acute given that most businesses are microenterprises.

Cultural ImpactsThe sustainability performance of tourism establishments in Bocas del Toro regarding cultural heritage is extremely poor. Currently, there is no cultural asset inventory, and establishments generally play a marginal role in promoting local culture. This leads to very low satisfaction with the design of policies and initiatives related to cultural heritage. However, there is significant potential for development [45]. The various islands of Bocas del Toro possess a rich cultural heritage, stemming from their historical past, Afro-Caribbean roots, and the presence of Indigenous communities outside of Colón Island, which could serve as a major cultural attraction [45].

Social ImpactsIn terms of the social impact, the lowest performance is related to tourism's contribution to the creation and improvement of services for the local community. The most pressing social gap is the minimal sustainability training provided to employees working in tourism [45]. This lack of education on sustainability, both among tourism workers and the general population, is a fundamental issue with significant implications for other identified gaps, such as efficient energy management, waste management, sustainable tourism practices, and the protection and conservation of natural and cultural heritage [43].

Ecological ImpactsThe analysis of the data collected from the service providers shows that the environmental dimension, represents one of the most critical sustainability challenges for tourism in Bocas del Toro. Key issues include low adoption of renewable energy, inadequate potable water supply, inefficient waste management, and minimal natural environment protection. If unresolved, these challenges could severely impact tourism, the region’s primary economic driver [45].

The most significant sustainability gap concerns the protection of Bocas del Toro’s natural environment [43]. This includes limited information on conservation status and ineffective management practices. Major concerns include the removal of entrance fees for protected areas, resulting in uncontrolled visitor numbers, and insufficient personnel from the Ministry of Environment, with only two staff members responsible for large areas. Additionally, popular tourist sites such as Bahía Delfines and Playa de las Estrellas suffer from overcrowding and lack of legal protection. Despite existing carrying capacity studies for some areas, they are outdated and not readily accessible to the public.

Infrastructure limitations also affect the provision of energy and water. While Colón Island has some electrical and water systems, frequent supply disruptions and poor water quality persist. Most establishments advise against drinking tap water. Compounding this issue is the lack of energy and water conservation practices in businesses—only 16% of establishments have water-saving plans, and 67% lack alternative energy sources.

Waste management is another challenge. While Bocas del Toro has made strides in cleaning streets and beaches, efforts to promote waste separation have been less successful. Vandalism has reduced the number of color-coded bins for waste differentiation, and improper use has led to undifferentiated disposal. Although a waste collection center on Colón Island exists and features innovative projects like glass recycling into pavers, it faces financial and logistical challenges. The center needs more support from local businesses and infrastructure improvements to ensure its long-term viability.

In summary, Bocas del Toro’s environmental sustainability is undermined by insufficient natural heritage protection, inadequate infrastructure for basic services, and weak waste management systems. Addressing these issues will require stronger conservation efforts, enhanced infrastructure, and better engagement of local stakeholders in sustainability practices. The question is to what extent the different stakeholders’ future visions of Bocas del Toro overlap to enable the co-creation of a collective vision driving the transformation. The future visions are discussed next.

Visions of the FutureThe question now arises as to what future visions the interviewees have of future development in Bocas. From these visions, it can be deduced what role sustainability considerations play now and how high the chances are that the groups will act sustainably in the future.

All locals respondents expect tourism to expand further in the future. Many respondents hope for more investment, a larger airport, higher tourism figures, more hotels and therefore more money. As a rule, this is linked to hopes for more income opportunities for the local population. To the question of “What would be your vision of what the island looks like?” the different stakeholders indicate the following:

Local: “I say it will be better. Better. More. More buildings, more venues, more restaurants. And more money, maybe”. L92.

One person expects further displacement of the population from the center to the interior of the island as a negative consequence of the increasing number of tourists. Others express wishes directed mainly at the government. It should set up a university, remove rubbish, develop the water infrastructure and ban cruise ships’.

The expats express contradictory visions for the future. While some hope that tourism will continue to develop and increase their income, others fear that Bocas will become a mass tourism destination that will lose its charm:

“But I think there are people who say that in ten years it will be like Bali. It could go in that direction. Personally, I don’t hope that will happen, but that it will keep a bit of the magic that it has now” E443.

Tourists expect the location to develop into a mass tourism destination in the future, with more hotels being built, uncontrolled urban sprawl affecting the environment, an increase in the number of tourists, and an expansion of services aimed at affluent individuals. Almost all respondents expect negative impacts from additional tourism development. More damage to nature is expected, which will significantly reduce the attractiveness of tourism.

Many expect the current atmosphere to be ruined by further tourism development: “I think if there were more tourists it would ruin the atmosphere” T264. It is expected that wealthy (foreign) investors will come and that the locals will benefit little.

The tourist service providers, including accommodation, were not explicitly asked about their vision of the future but it emerged during the interviews. As with the tourists, the interviewees were concerned about the increasing negative impact that the growing tourism is having on the island in terms of the conservation of the natural and cultural heritage. Nonetheless, and from the perspective of the interviewees, the economic benefits that are expected from tourism seem to compensate the negative ones.

Looking at the results of the interviews, a superficial glance might lead to the conclusion that the tourism-related transformation of Bocas del Toro is considered to be sustainable. All the groups interviewed reported many positive effects, especially in economic terms. However, a deeper analysis reveals contradictory statements, inconsistencies, and blind spots in the reports, which will be discussed below.

ContradictionsParticularly contradictory are the interviews with locals who feel that they benefit from tourism through jobs and income opportunities, improved infrastructure, and cultural contact. At the same time, these interviewees report many problematic developments that affect their daily lives, such as forced resettlement, displacement due to increased cost of living and property prices, inadequate infrastructure (water, electricity, roads), increasing crime, waste pollution or loss of access to the beach. Despite the many problems, tourism is viewed very positively and further tourism development is favoured. On the one hand, this is probably due to the fact that respondents compare the current situation of Bocas with their knowledge of the town’s past as a poor fishing center and, against this background, find the current situation better than the previous one. In addition, many of the perceived negative developments are not attributed to tourism, but to politics or retail.

Many of the tourists surveyed also perceive the current impact of tourism as predominantly positive. This contrasts with the future expectations, who are extremely negative about the further development of tourism. This can be explained by the contradictory desires. Many seem to want to experience nature in a lost, unspoiled paradise [48], but at the same time they want all the amenities and tourist services. These different desires may become difficult to reconcile if the number of tourists continues to increase in the sense of overtourism [5] and many of the negative effects of mass tourism get out of hand. Therefore, balancing economic growth, environment conservation and social well-being are the biggest challenges tourism phase in the Latin America region [19].

Expatriates’ statements are also contradictory, as they want to benefit from further expansion of tourism and increased tourist numbers, while at the same time maintaining their own nature-based lifestyle and good relations with local people who feel many of the negative effects of expansion.

RisksThere is a general lack of awareness among all groups regarding the ecological impacts of tourism, with little mention of ecotourism as a sustainability driver [49]. Key environmental issues such as waste, coastal erosion, water pollution, deforestation, coral loss, and threats to marine species are rarely acknowledged, except by eco-tourism specialists in areas outside Colón Island (e.g., Bastimentos and San Cristobal). Climate change impacts, like sea level rise and extreme weather, are also poorly understood by respondents, with no adaptation strategies in place. This is concerning since tourism cannot be sustainable without ecological responsibility. Continued pollution risks driving tourists away, harming the local economy.

None of the groups interviewed assume responsibility for these issues, mirroring findings from Costa Rica that tourism is ill-prepared for climate risks [50]. Additionally, social, and cultural problems like displacement and community disruption, though not yet widely attributed to tourism, could negatively affect the local attitude toward tourists in the future.

Infrastructure development, particularly roads and resorts, is viewed positively, but unchecked expansion could harm natural resources, without mitigating environmental solutions such as waste management facilities. The unchecked growth in tourism is seen as unsustainable by some experts, who advocate for limiting tourist numbers [51].

While tourism is economically beneficial, locals remain dependent on low-paying jobs, with non-local investors reaping most profits. Rising costs of living, linked to tourism, exacerbate local inequalities, which may worsen over time. Tourism’s contribution to poverty alleviation and local empowerment remains questionable, as local political participation in tourism development is minimal. Sustainable tourism requires collaboration between businesses, communities, governments, and tourists [28], with shared responsibility for maintaining a healthy environment crucial for tourism’s success.

OpportunitiesDespite the risks, the data reveal that there are still many opportunities to positively influence the transformation process in Bocas del Toro so that the typical effects of overtourism do not occur and sustainable forms of tourism can become established [5]. The business structure in the tourism industry is still characterized by many individual or small businesses (see results section), and there are hardly any large international chains. This provides an opportunity for entrepreneurs to have a strong local connection and to seek to strengthen local communities, adapt architectural styles to local conditions and use profits locally. In addition, there are still intact ecosystems in many places on the islands that can support a wide range of ecotourism activities. However, there is an urgent need to protect natural resources by changing the practices of all those involved, for which information and education are possible tools.

Many of our interviewees from all groups reported friendly exchange relationships between expats, locals, and tourists, which offers the opportunity to include the knowledge, perspectives, problems and wishes of all in the development of solution relationships, although this would require more moderation and governance involving the local population [18]. In this context, it is positive that the development of ecotourism is also viewed positively by the government [52] and may be supported in the future (see introduction). In a study done in Dominican Republic on sustainable tourism (Peña, n.d.), the majority of the entrepreneurs working in tourism activities agree about the need to include communities in the decision making process and in the protection of natural resources. Thus, ATP needs to promote a more integration of communities in programs and projects with the help of other tourist key holders.

This study set out to explore how different stakeholders in Bocas del Toro perceive tourism’s impacts and sustainability, and what these perceptions reveal about the region’s prospects for a sustainability transformation. Drawing on transition theory and a multiperspective methodology, we found that while tourism is widely acknowledged as economically beneficial, stakeholders’ visions for the future diverge significantly, especially in their recognition of ecological and social risks. These divergent visions limited mutual understanding, and weak mechanisms for co-creation constitute serious barriers to sustainability transformations.

Our analysis shows that while locals, tourists, expats, and service providers share some appreciation for the region’s natural beauty and tourism-driven income, they hold conflicting views on its cultural, environmental, and social dimensions. Ecological impacts—such as pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate threats—are consistently under-recognized or misattributed, echoing concerns raised in the literature about the social blind spots in sustainability transitions [52]. Furthermore, trust in public institutions is low, and there is little evidence of meaningful stakeholder collaboration, limiting the capacity to co-create shared visions or act collectively- key preconditions for transformative change [25].

These findings reveal a fragmented landscape of responsibility, where different groups perceive benefits and risks in isolation, and long-term sustainability is undermined by short-term gains. In line with Ramkissoon’s model [24], the absence of place attachment and trust hinders pro-environmental behavior and collective support for sustainable tourism. Without mechanisms to build alignment across perspectives, the risk is not just overtourism but the erosion of the ecological and cultural assets that underpin the tourism economy itself in Bocas del Toro.

To move toward a more sustainable tourism future in Bocas, it is crucial to address these structural and perceptual gaps. Strengthening local governance capacity is essential—not only to regulate growth, but to facilitate inclusive platforms where diverse voices can co-create the region’s tourism vision [23,25]. Educational and behavioral interventions that promote ecological awareness and cultural sensitivity among tourists and residents can help bridge attitudinal divides [27]. Equally important is the diversification of tourism offerings—moving beyond the dominant “sun and beach” model to embrace ecotourism, cultural heritage, and community-based experiences that reflect the region’s unique assets and social dynamics [18].

As transition theory emphasizes, sustainability transformations are not simply about adopting new technologies or standards, but about shifting worldviews, relationships, and governance practices [17]. In the case of Bocas del Toro, this means creating the conditions for shared learning, negotiation, and long-term collaboration across stakeholder groups. Sustainability will not emerge from policy declarations alone, but from deliberate efforts to build mutual trust, strengthen place-based attachments, and empower communities to actively shape their tourism futures [26].

In conclusion, the sustainability of tourism in Bocas del Toro hinges on a shift from fragmented understandings and extractive development toward more relational, participatory, and regenerative models. Achieving this will require sustained investment in dialogue, trust, capacity building, and inclusive governance that bridges perspectives and aligns local aspirations with ecological and cultural resilience.

Conceptualization, AB and CC; Methodology, AB and CC; Data collection and analysis: AB, CC, MAdN; Writing—Review & Editing, AB, CC, MAdN; Supervision, AB and MAdN.

The authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the students who helped to conduct the interviews and the student assistants at the University of Cologne who supported the analysis, in particular Georgina Schneider, Pascal Muschik and Hila Maluk. We would like to thank especially Jaime Cabré who collaborate with the research design and planning of the fieldtrips to collect the data. We thank also, the students Joseph Castillo, Stephanie Hernandez, Agustin Rodriguez, Miguel Otero, Jose Serracin, Maikol Botacio y Nayreth Walachosky, who helped conducting the surveys. Especial thanks to the authorities of the University of Panama for their support.

The feedback received by Leda Peralta, Marisela Bonilla and Lizzete Gil to previous results of the project contributed significantly to the quality of the final report. A particular thanks goes to the team of the Autoridad de Turismo de Panamá for their support with the collection of the data and the organization of the fieldwork.

Cristina Chaminade would like to acknowledge the funding received from UN-ECLAC for the project “Caja de herramientas para la medición de la sostenibilidad en destinos turísticos de Panamá con propuestas de política pública para cerrar brechas de sostenibilidad”.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

Budke A, Chaminade C, Adames de Newbill M. Sustainability transformations in tourism destinations. A deeper look at commonalities and differences in Stakeholders’ perceptions in Bocas del Toro, Panama. J Sustain Res. 2025;7(3):e250048. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20250048.

Copyright © Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions