Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

J Sustain Res. 2024;6(2):e240019. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20240019

1 Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Volos 38333 Greece

2 Department of Economics, University of Thessaly, Volos 38334, Greece

* Correspondence: Theodore Metaxas.

The place of Thermopyles Battlefield is registered as one of the most famous and well-known sites of the ancient military history and introduced as a potential magnifying point of attracting visitors. Due to the historic magnitude of the event as a military tactic and the symbolic meaning of the strongly bravery sacrifice of King Leonidas, the 300 Spartans and the rest Greek warriors as a idealistic heritage aspect like the fight for freedom against tremendous barbaric forces, there is locally oriented ongoing stakeholders discussion concerning the appropriate development steps of the specific place as an asset of sustainable economic procedure. Dark tourism and battlefield tourism formulate the general wider context of explaining the interest of stakeholders planning process and tourist visiting motivational factors. The aim of this research is to record the existing parameters and examine the possibilities and prospects for the development of Thermopyles as a site of competitive local identity and a branding place of the future sustainable tourism development. This is achieved through a qualitative method of face-to-face semi structured interviews with 23 local stakeholders, planners and professionals who actively participate in the local economic arena and struggle about the exploitation of a globally famous tourist point as a dark tourism multiplier.

Visiting places of battlefields has been recently developed into a dynamic tourism prospect, as visitors seek information about the history and the cultural heritage of famous battle sites [1]. However, a small number of battle sites managed to emerge in attractive and dynamic tourist destinations due to the fact that the lack of presentable exhibits and the absence of monuments at the battle sites fail to support the desire of interested visitors to ‘read’ the battle sites satisfactorily [2]. The site of the Battle of Thermopyles (480BC) is recognized as one of the most famous sites of the historical battles as it is considered to have played a key role in saving Western civilization [3]. At the same time, it is today an important point of attraction for visitors and tourists in the wider region [4]. The visitor can walk through the archaeological site of the battle of Thermopylae, visit the statue of Leonidas, the Kolonos Hill and as well as the Thermopylae Historical Information Center and the thermal spring of Thermopyles.

The main purpose of this paper is to examine the potential and development prospects of the local bodies approach concerning the exploitation of the tourist interest in the battle of Thermopyles and the name Thermopyles in the light of dark tourism and battlefield tourism. The methodology is based on conducting qualitative research through 23 semi-structured interviews with the representatives of active local bodies and organizations in the wider local area of the empirical research. All the interviews were carried out between March 1, 2023 and May 31, 2023. The average duration of the interview was estimated at half an hour and due to the open process in some cases it was completed within an hour.

The approach of local bodies to the issue of the exploitation of the battle of Thermopyles and the management of the name has been little examined. The research field covers the overwhelming majority of the views of the local bodies as the questionnaire was addressed to all the local bodies of the wider region as well as bodies that are professionally active in the area. The approach of the local bodies to record and highlight the battle of Thermopyles and the name Thermopyles through the general dimension of dark tourism and battlefield tourism could be described as pioneering, as no corresponding research on dark tourism and battlefield tourism has been recorded in the past to the local bodies for Thermopyles. At an initial stage, the benefits from highlighting the archaeological site of the battle of Thermopyles as well as the individual elements resulting from the historical and symbolic elements of the site can stimulate the local economy and significantly strengthen the tourism profile of the area through sustainable investment options. Additionally, the utilization of the thermal springs can improve the touristic infrastructure and strengthen the local economy. Through the interviews the existing situation has been recorded as well as the significant development perspective of the area but with the minimal to no contribution of the conditions of dark tourism and battlefield tourism.

The highlighting of the distinct and special characteristics of a region, a place or a country is presented as an imperative object in order to exploit the special and valuable competitive advantages of a place and to build a competitive identity [5]. Govers [6] argues that the creation of a brand should be part of a more general strategy and focus on competitive identity, as branding is related to identity and identity is significantly influenced by local population, culture, heritage, symbolism, leadership, collaborative sense of belonging and heterogeneity. Ashworth [7] states that place branding describes the idea of discovering or creating some special and characteristic elements of an area, which contributes to the differentiation of the specific area from other places due to its uniqueness and undoubtedly contributes to the creation of competitive brand value. Karachalis [8], argues that the term place branding refers to the attribution of a specific spatial identity to a region or city based on its particular characteristics and to the creation of a central idea of their promotion. Dion and Borraz [9] argue that managers of branded heritage sites have at their disposal tools for the “sanctification” of each heritage site such as the history of the site, the construction and dissemination of stories and myths, the establishment of special ritual events and the determination of special areas of prohibited access and accredited entry. Ujang and Zakariya [10] refer that the combination of the element’s physical form/structure, activity and the produced meanings are extensions of the value of a place. The main factors of sense of place are place, products and people [5]. Kalandides [11] refers to the integrated form of place branding of a place to improve the image of a region, which considers various parameters such as the material elements of the place, institutional bodies, practices and representations. Zenker & Braun [12] define the place brand as: “A place brand is a network of associations in the place consumers’ mind based on the visual, verbal, and behavioral expression of a place and its’ stakeholders. These associations differ in their influence within the network and in importance for the place consumers’ attitude and behavior”.

Braun et al. [13] refer to the place brand as the government strategy of projected images and the management of perceptions of the place. Anholt [14] points out that place branding is nothing more than the practical application of a brand development strategy and other marketing techniques in accordance with economic, socio-political and cultural developments in a city, region and country. Govers [15] points out that branding is essentially about managing the reputation of a place and should not only be related to standard marketing tools such as a logo or slogan but should focus on the ability to present the distinct characteristics of a place and how they are made perceived by consumers.

Hanna et al. [16] state that place branding is necessary due to the growing power of international media, low cost of travel, increasing disposable income, the threat of place equalization, international investors, competition for skilled personnel and the demand for a diverse offering cultural products and low-cost global media. Anholt [17] argues that place branding is significantly influenced by globalization processes where the marketplace of ideas, culture, reputation, in addition to products, services and capital merge into a single global community. A definition of the destination brand could be the sum of the individual existing perceptions about an area (experiences, hearings or prejudices), which influence the general attitude at an emotional level. A destination’s brand is unique, responsive to reality and formed in the eyes and mind of the visitor. In essence, a destination is a brand when it develops, presents and communicates its main positive characteristics to the key audience and creates the conditions for the creation of a reputation. The process of developing a brand is a long and painful process that includes individual activities such as market segmentation, SWOT analysis, competitor analysis, consumer behavior and market research data, stakeholder engagement, brand development activities, results monitoring and feedback [5]. According to Milicevic et al. [18] the process of destination branding is related to the achievement of an increased degree of competitiveness of the destination while the degree of tourist satisfaction is positively related to the level of branding and the effort to satisfy the tourist needs. San Eugenio-Vela J, et al. [19] state that stakeholder involvement and participatory governance of place branding are closely related to each other in terms of place branding and spatial planning. According to Anholt’s theory of competitive identity governments and organizations that act through an integrated coordination plan of the individual parameters of the hexagon (tourism, manufactured and exported branded products, general applied policy, investment policy, people and culture in general) create the conditions and build a more competitive image and identity for the country and the wider region [5]. Following to Karachalis [8] the cultural heritage of a place, modern culture and leisure activities are important components of the dominant image and identity of a place as they contribute dynamically to the economic development of the area. Elements of culture such as museums, monuments as well as cultural events, exhibitions, festivals and major events are modern tools for highlighting the advantages of a place and promotional activities for place marketing. Zhang [20] details the transformational steps of Taiwan’s Kinmen Island as a battlefield tourism destination and describes the efforts of local authorities, residents and local businessmen to highlight the core identity of the place as a place of battlefield tourism destination. Noivo et al. [21] state that creative tourism with tools such as battle re-enactment and living history are drivers of battlefield tourism success and empower local community members’ participation, collaborative networking, sustainable development, local identity and memory. Park [22] states that the heart of the nature of heritage tourism is deeply connected with the contemporary use of history and the past.

The role of local government bodies is decisive for the achievement of local economic development and is closely related to the place marketing [23,24]. Place marketing can be considered as an effective tool for highlighting the competitiveness of an area, provided that strategic planning processes are developed and implemented and development policies are implemented by the local actors involved [23] and should not be considered as an opportunistic process of promoting an area [25,26] but as part of a broader strategic plan for place development which involves the synergy of different perspectives, approaches and capabilities [26,27]. Cleave et al. [28] argue that ‘place branding’ process is part of local economic development. Policy makers, local bodies representatives and local businesses should emphasize in the provision of high quality experiences with positive economic outcomes and respect for the protection of the environment, society and cultural heritage [29,30].

The existence of a total number of tourists does not necessarily mark an area as a thriving tourist destination. The highlighting of a destination as a tourist destination should be based on remarkable possibilities and characteristics. The existence of the following ten characteristics, known as ten A of Morrison [31], could characterize a successful tourist destination based on identity: Awareness, Attractiveness, Access, Appreciation, Assurance, Activities, Appearance, Action, and Accountability. Aitken & Campelo [32] discuss the importance of the community in the place branding process and propose four key elements of importance: rights, roles, relationships and responsibilities (also known as 4R rights, roles, relationships, and responsibilities).

Dark Tourism and Battlefield TourismThe desire to visit places where events of loss of life or tragic incidents have occurred is not a modern and recent phenomenon but has also been recorded in the past as a choice of visiting for pilgrimage reasons. The concept of dark tourism [33] covers all cases of visiting places where death, fear, or some unpleasant tragic events have taken place. Fonseca et al. [34] state that research interest in examining dark tourism as part of tourism economic activity began in the early 1990s and various researchers turned their attention to tourism in places of death or suffering by including various concepts and approaches such as: ‘Black Spot’, ‘Thanatourism’, ‘Atrocity Tourism’, ‘Morbid Tourism’. Nowadays, the power of press and mass media help to spread the events on a global scale. Stone [35] argued that the studying the visitor’s experiences in places of death could lead to the definition of a different aspect of dark tourism. Light [36] states that research interest in dark tourism initially focused on cultural tourism while in recent years it has been related to different aspects demarcated at scientific levels such as sociology. Stone [37] classified the tourist destinations based on the intensity and depth of “darkness” (spectrum).

Tourism in places where historical battles have taken place consist one of the main categories of dark tourism. Fonseca et al. [34] distinguish War/battlefield tourism as one of the main sub-categories of dark tourism and mention a number of dark tourism spots of global interest. Travel to war zones for the purpose of both sightseeing and historical studying about the war conflict. Battlefields are particularly important as sites of memory that elicit collective memories of historical experiences associated with warlike activities. In this context, battlefields, cemeteries, monuments, museums, etc. are used as resources to develop a wide variety of tourism products and related infrastructure. War tourism is nothing new. Shirley et al. [38] refer to four recent cases of destinations on four different continents and used different strategies to attract visitors with the ending of various conflicts in the last decade of the twentieth century. Cooper [39] supports that history of World War II has transformed many sites into both wartime and peacetime tourist attractions; such as Pearl Harbor, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb memorials, and other battlefield sites in the South Pacific.

Mitchel et al. [40] include monument tourism and battlefield tourism in sub-categories of dark tourism. In more detail, they state that ‘memorial tourism’ refers to locations linked to historical events that are part of collective memory and their main characteristic is the fact that commemoration plays a leading role. However, certain sites such as battlefields, cemeteries, concentration camps or prisons are considered subcategories of dark tourism. ‘Battlefield tourism’ is a category of dark tourism that involves visits to known war sites, battlefields and cemeteries. This trend was maintained and increased after World War I, where many attractions that include not only battles and related monuments and cemeteries, but also countless monuments, museums and other structures and places commemorating wars, battles and related events or atrocities attract many visitors [41]. However, visiting dark places and places cannot be a point of modern history, as a visit to Auschwitz or Chernobyl might be, but extends to the ancient journeys of the past such as Roman-era Colosseum performances or martyrdom, visit to medieval torture sites [42]. Hertzog [43] argues that the reenactment of battles in the 1970s began in French regions through the initiatives of local organizations and residents and Foulk [44] states that France's economy benefits from the ‘economy of history’, as many regions have been affected by the operations of World War I and II. Historic Environment Scotland (HES) [45] created a digital repository of the country’s historical battles that includes a database of the most important information. Table 1 presents cases of battlefield tourism with branding features.

Visitors EngagementAccording to Stone [55] the motives for visiting places of dark tourism concern the tourist’s desire to come into contact with the macabre. Biran et al. [56] distinguish four groups of dark tourism motivations: (1) field verification, (2) learning, (3) visiting famous attractions and (4) emotional experience. Emotional experience and cognition are positively related as well as cognition to behavioral intention [57]. Austin [58] states the sensitive character of tourism development in sites with diverse historical events. The nature ofvisiting sensitive historical sites highlights issues concerning the visitor’s emotional state about the place, previous expectations, as well as issues such as what to learn, what will be the perception of the presentation and interpretation of the place. Additional important issues are the ease of access to the site and the existence of social experiences between groups of visitors. Stone [55] supports that dark tourism tourists are interested in entertainment except education, while Sharpley & Stone [59] report more dark tourism destinations offer recreational activities. Basarin & Hall [52] cite a number of reasons for visiting Gallipoli commemorations, the most important of which are to express gratitude for freedom, to attend a ceremony, and to pay tribute.

Miles [54] concluded that battlefield visitors at four UK battlefields cannot be assessed as tourists attracted to sites with a high and heavy degree of darkness as the nature of the attractions is commercial and the visitor experience is casual and dominated by a lighter set of values. Hosseini et al. [60] identified four key factors influencing dark tourism experiences in a destination: (1) learning from dark experiences, (2) spiritual experiences, (3) participation in activities, and (4) emotional experiences. Visitors to battle sites come with a variety of motivations and expectations. An important success factor is the satisfactory provision of information, the creation of emotional ties with the location and the offering of personalized services to different customer groups [2]. Interest in national and military history as well as a desire to participate in historical battles re-enactments are important motivations for participating in battlefield visits. Additional reasons for visiting a battlefield site could be personal or family ties related to the site of the battle or the desire to visit a place that has been marked by an individual or collective interest. Finally, visits to battle sites can be part of a youth awareness and history learning policy. García-Madurga & Grilló-Méndez [1] point out that visitors to battle sites come with a variety of motivations and expectations. An important success factor is the satisfactory provision of information, the creation of emotional ties with the location and the offering of personalized services to different customer groups. Winter [61] states that battlefield commemorations and tributes has been introduced after the decision of the British War Commission of First World War 1914–1918 to bury the war dead on the battlefield.

Sustainable Development and Impacts of Visiting Places of BattlefieldThe tripartite of sustainable management economic efficiency, social justice and environmental protection ensures harmonious tourism development as sustainable and environmentally beneficial through a step-by-step process of approach followed by the interested and involved bodies intervention and evaluation. The attractiveness of a tourist destination is also systematically based on the reputation created by the local characteristics (uniqueness and quality of cultural and environmental resources, local tradition, customs, values, hospitality, etc.). Therefore, sustainable tourism development requires the systematic preservation of the local advantage (cultural, environmental and folkloric wealth) with protection systems against the problems of mass tourism [62] and the comprehensive coverage of the needs of tourists and places of hospitality while protecting the future resources and opportunities [63]. The concept of sustainability is based on the participation of the inhabitants in the way of promoting and promoting the place. At the same time, the role of the stakeholders in the process of creating the brand of the place is also considered very important.

The use of tools such as targeting groups and structured questionnaires can contribute positively to the process [64]. Battlefield tourism generates significant economic benefits through consumer demand, job creation and cultural heritage issues [1]. According to American Battlefield Trust [65] visits to battle sites have economic, social and environmental impacts. Visits to battlefields have boosted the local economy by raising demand for sightseeing, accommodation, food, transportation and entertainment services. The economic, social and environmental impacts of visiting famous battlefield sites in USA state that primary and first time visitors decide to spend more than 1.5 days on the battlefield sites and support local businesses, employing and local taxes reception by increasing spending [66]. Also, Battlefields parks strengthen community bonds and bring together a large number of people of different interest groups linking ‘visitors’ relationship with the history of a place and the history of the nation. Visits to battlefields contribute to the preservation of the natural environment as well as the preservation of cultural and historical heritage [65]. Finally, protection and preservation of the natural environment, the protection of ecosystems, water and fauna, as well as maintaining the principles of sustainable development and strengthening agricultural production are the main environmental effects [65].

A battlefield is a complex concept in space and includes many kinds of space, from the physical to the symbolic. The current form of a battlefield landscape often remains a ‘silent’ witness to history, unable to successfully convey and render the past into the present. Attracting a wider number of visitors has turned battlefields into popular tourist attractions and makes more imperative the need to present the story of a historical landscape in a general battlefield tourism narrative in order to justify the need to use specific tourist facilities and achieve the transfer of the past to present state of today’s landscape [67]. In fact, a short number of cases managed to turn into successful tourist attractions due to the lack of exhibits and the inability of tourists to perceive the exact characteristics and data of the site [2].

Battlefield tourism is a recent phenomenon, which first began in the early 19th century with visits to the site of the Battle of Waterloo and is now an important economic activity [52]. The inscription of Simonides [41] at the site of Thermopylae (480 BC) in honor of the warriors of Sparta is, among many other places, a famous, well-known and interesting monument particularly popular with tourists. Nowadays, visiting battlefield sites has become a popular form of travel and can form an important educational tool for transferring knowledge and information about history and cultural heritage, while visitor interest is broadening in battle sites of ancient history. The best practices for battlefield tourism include the involvement of experienced tour guides, the application of storytelling techniques and the use of promotional tools that offer interactive experiences and attract visitors such as reenactments [1]. Chylinska [67] mentions the importance of tangible and intangible elements of battlefields. However, the attempt to adapt battlefields to tourist attractions presents a series of difficulties and problems, which are not limited to technical issues only [2].

The process of developing a brand is a long-term process that includes specialized actions, among which is the mapping of strengths and weaknesses as well as opportunities and threats (SWOT Analysis) [5]. Zhang [20] studied the case of Kinmen’s branding example and mentions the result of local authorities’ efforts and the implementation of a bottom-up practical plan by local businessmen, residents and tourists, while Farmaki [68] concludes that dark tourism supply and demand need to be explored together and highlights the importance of marketing tactics in developing and promoting dark tourism. Bozamanoudi [69] reports no positive tourism development for the area Thermopylea in the last period with main reference to the last 10 years despite the fact that the area is known for its history. Noivo et al. [21] states the role of creative tourism and supports that “living history” enhances the interactive contact with the local culture. Dunkley et al. [70] refer that battlefield tours offer opportunities for pilgrimage, collective and personal remembrance and validation of events, while battlefield tours are described as enriching, meaningful, and in some cases life-changing experiences. Virgili et al. [49] concluded that the commercialization of the site Battle of Verdum can gradually take a more complex form over time as it is significantly influenced by the degree of stakeholder involvement and their behavior. Hertzog [43] argues that the reenactment of battles in the 1970s began in French regions through the initiatives of local organizations and residents. Foulk [44] states that France’s economy benefits from the ‘economy of history’, as many regions have been affected by the operations of World War I and II. Winter [61] states that battlefield commemorations and tributes has been introduced after the decision of the British War Commission of First World War 1914–1918 to bury the war dead on the battlefield. Upton et al. [71] concluded that tourists seek to maintain contact and create experiences with war zones. Proos and Hattingh [72] investigated the potential for the development of dark tourism in the Karoo region of South Africa through a thematic route that would unite most of the battlefields of the war South Africa of the period 1899–1902 and the establishment of a promotional organization.

Kennell & Powell [73] tried to analyze the relationship between dark tourism and World Heritage sites and sought to assess stakeholder perceptions of the potential for World Heritage site development (Greenwich Maritime, WHS) as a dark tourism spot. Volcic et al. [74] report that the city of Sarajevo has been transformed into a tourist attraction through the convergence of authentic memories and ‘war traumas’ of the recent past. Franch et al. [46] explored the role of local communities and stakeholders in the recognition, promotion and exploitation of war heritage sites as well as the role of place identity and cultural identity in two provinces of northern Italy that have war heritage sites such as fortifications, trenches and battle testimonies of the Alpine War during the Great War (1914–1918) (Trentino and Alto Adige/Südtirol). Irimias [47] states that trying to create memories of a war conflict can create an emotional connection to the wider space. Films, artistic creations and thematic routes aims to help cultural tourism and heritage tourism [46].

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the possibilities and development prospects of the Thermopyles brand name for the benefit of the local economy. To address the research question, and having in mind the lack of literature on the development of important dark tourism points of interest for the Greek context, primary research was carried out using interviews. The use of qualitative interviewing helps to capture the entity of the social world through the recording of people’s experiences, opinions, interpretations and interactions. The qualitative interview has positive points of reference as it not only helps in the in-depth exploration of perceptions, opinions and values but plays an important role in understanding the complexity of human experience and behavior and penetrates the phenomenon under investigation through an active and interactive perspective of the interviewees [75]. The semi-structured in-depth interview is often used by new qualitative researchers and involves a set of predetermined research questions to comprehensively cover the research topics. It is noted that this particular type of interview presents degrees of flexibility concerning the content of the questions, the need to deepen individual aspects of the questions, the order of discussion as well as the addition and removal of questions.

One of the main aims of the interview is to provide the researcher with a wealth of data on people’s perceptions, thoughts and impressions through an informal atmosphere of encouragement and dialogue [76]. Richards (as referred in Anyan) [77] states that qualitative data are records of observations, descriptions and narratives that display a degree of complexity. According to Kedraka [78] interviews “enlight” the way others see things, their thoughts, attitudes and opinions behind their behavior meanwhile Paraskevopoulou-Kollia [79] state that interview concentrates at the center of qualitative research and relies on direct communication between researcher and respondent. As Dunkley et al. [70] also attempted, for a better understanding of the interview elements, a more open and discrete approach was followed to record opinions and responses through open-ended questions and increased interactivity [80].

The research questions posted to the local bodies were the following:

RQ1. What is your knowledge about the point and what is your valuation? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ2. What are the resources available to develop (dark) tourism services at the site? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ3. What are the current (dark) tourism offers on the site? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ4. What are the possible products or experiences offered regarding tourism (dark) at the point? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ5. Do you believe that a tourism market has been created for this point? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ6. What are the main strengths and weaknesses and the main opportunities and threats for the site? UNWTO [5].

RQ7. What are the kinds of tourism activities (other than dark tourism) that would be acceptable to develop locally? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ8. What was possible and desirable in terms of local tourism development? Kennell & Powell [73].

RQ9. What is the connection between the point and historical and cultural heritage tourism? [46].

RQ10. What are the actions of local authorities including to promote and communicate the point in combination with cultural products? [46].

RQ11. What is your opinion about the establishment of a specialized organization to promote the point as a destination? [72].

Thermopyles constitutes the site of the historic battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC and is registered as one of the most significant and valuable archaeological resources for the tourism sector of the Region of Central Greece [4]. Museums and archaeological sites of Central Greece attract a large number of visitors [4] while the main categories of regional tourism product are: Sun and Sea, Cultural-Religious Tourism, Shipping, MICE, City Breaks, Medical Tourism. The prefecture of Fthiotida is mainly focusing on Sun and Sea and Cultural-Religious Tourism [81].

The famous battle of Thermopyles is considered as a very strong attractive pole and motivation for visitors and is recognized as a symbol of world historical value. The visiting experience presents the values of Pride, Power, Tradition, Superpower and Supremacy. The visit includes the tour of the battlefield and the statue of Leonidas and the combined visit to the hot waterfall of the thermal springs and points of archaeological and religious interest. The main categories of visitors are couples aged 35–34 and families aged 35 and over and come from the USA, France, Italy, etc. countries, while many visitors also come from Greece, etc. [81]. Bazani [82] reports that Thermopylae is the main monument for the development of dark tourism in the Fthiotida as 41.2 percent of the respondents answered positively. Also, other important and historical battles have taken place in Thermopylae Pass such as the defense of Australians and New Zealanders against German troops (April 22–24, 1941) and the greek guerrillas (ELAS) with the Germans (September 1943) [83].

According to Dakoronia [84] the excavation research by Professor Spyridon Marinatos started at 1939 and has been funded by the American Elizabeth Humlin Hunt. The statue of King Leonidas has been created by the sculptor Falireas and inaugurated at 1955 with initial funding from the Greek-American expatriate Dousmanis and the contribution of the 300 Greek-Americans of AHEPA headed by Mr. Bouras who offered 300 dollars each, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. AHEPA’s Greek-American donors on the day of the inauguration of the Leonidas monument. Source: Dakoronia [84].

Figure 1. AHEPA’s Greek-American donors on the day of the inauguration of the Leonidas monument. Source: Dakoronia [84].

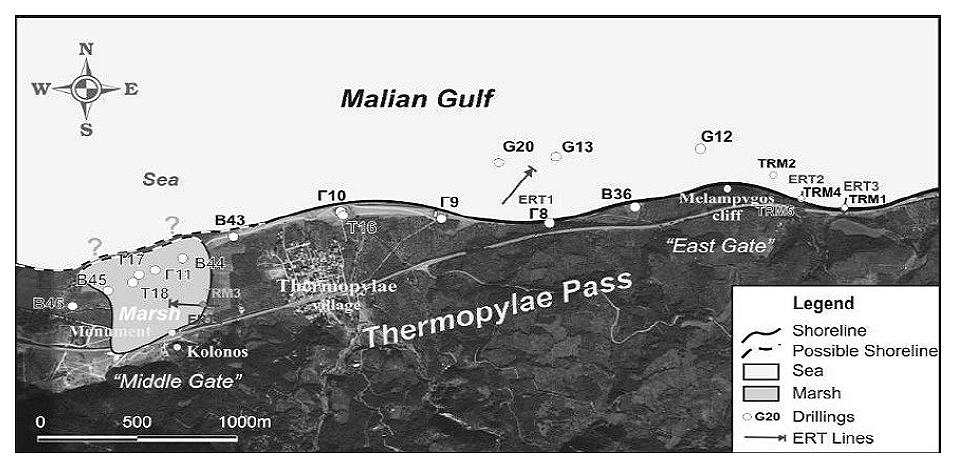

Vouvalidis et al. (2010) [85] report that overtime there were changes in the morphology of the battle ground due to the alluvium of the Sperchios Potamos and they concluded that Herodotus’ descriptions that the eastern passage was closed by the sea and marshes are confirmed. Characteristically, they state that the results of their research confirm the existence of a freshwater marsh in the middle passage which was fed by the hot water of the thermal spring at the sea level, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Theropyles Pass (at the battlefield period). Source: Vouvalidis et al. [85].

Figure 2. Theropyles Pass (at the battlefield period). Source: Vouvalidis et al. [85].

Western civilization would be different and almost unrecognizable if the historical event at Thermopylae (480 BC) has not been occurred during a war conflict between the powerful Persian Empire and the Greek alliance of small city-states defensing ideals, freedom and independence. It is the time where the legendary King of Sparta Leonidas replied the Persian pantocrator Xerxis with the historic phrase “Molon Lave” (Come and get them!), when the Persian King demanded the immediate surrender of arms [3]. Zouboulakis [86] describes the important moments of the battle of Thermopylae, which lasted three days. From the first day, the effective defense of Spartans with the shield, the phalanx formation and the two meters spears (till the appearance of Efialtes and the last stage of attack on Kolonos Hill.

SWOT Analysis of ThermopylesThe main strengths and weaknesses as well as the main opportunities and threats of the Thermopyles site, are presented in Table 2. The main strengths are the natural environment, the recognition of the famous name as well as the individual elements of archaeological and historical interest. Also, a positive element is the symbolism. The main weak points are the underutilization of the point and the lack of an integrated development plan. Another weak point is referred the problematic image of the thermal springs and the lack of strategic promotion and promotion of the whole area. Some references concern the operation of the refugee accommodation spot in negative way regarding the contribution to the deterioration of the image and degradation of the area. The opportunities concern the future perspective of area development and the possible combination with other tourism activities as well as the supply of specialized products and services. The threats regard the non-utilization of the point, the absence of investment plans and interventions in general in conjunction with the discrediting of the site and environmental degradation.

Research—InterviewsThe list of representatives who responded positively consists of 23 local bodies that are directly or indirectly involved in the local economy, are related to the planning and development of local tourism and have a significant experience and knowledge on the subject of Thermopyles. The bodies consist of 11 public sector bodies and 12 private sector bodies, while the field of activity is from public organizations, tourism sector, mass media, scientific sector as well as specialists in tourism, local culture and cultural specialists and sports activities. The survey was sent via e-mail to representatives of local bodies in the wider area of Thermopyles and in particular to bodies that have their headquarters in the Municipality of Lamia and in general in the Regional Unit of Fthiotida. The representative of each organization that responded was then contacted and the place and time of the interview was determined. For reasons of saving time, some organizations chose to send their answers in writing. The questionnaire was also sent to organizations that do not have their headquarters in the Municipality or the Region, but operate in the area of Thermopyles.

This section presents the results of the interviews of the 23 representatives of local bodies that participated in the process.

Knowledge about Thermopyles—Site ValuationThermopyles is recognized by all respondents as a site with significant level of historicity due to battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC between the Greeks and the Persians. The existence of thermal springs and geothermal potential is also a point of interest. The site is archaeological and is known for the statue of Leonidas, the hill of Kolonos, the Phokian wall as well as the Information Center. Nine of the twenty-three respondents mention the global recognition of the point, while 14 of the 23 respondents state that the site of Thermopyles is a pole of attraction for tourism with significant growth prospects. LP1 refers:

“It has a wealth of rare beauty both in terms of historicity and geothermal energy. The truth is that it is a burning desire of all of citizens as well as the Municipal authority to utilize the area on the one hand for the development of the tourist product based on the historical and cultural heritage and on the other hand for the promotion of thermal tourism”.

LP7 highlights the point and its historicity and mentions:

“It is a historical site which combines at the same time the possibilities of tourist development due to the thermal springs. An international brand name that, at least for the last 50 years, has been constantly getting cheaper despite whatever opinions are heard in between about its utilization. It is an area of about 800 acres that combines thermalism with culture and ancient history. It is on the Athens-Kalambaka axis wherea large stream of imported tourism moves and on the Delphi Kalambaka axis that also moves a particularly large tourist stream”.

The symbolism of the place stands another important parameter; both as a symbol of freedom, bravery and self-sacrifice as well as a symbol of highlighting the ideals of Western civilization. The future prospects for economic development are mentioned by many representatives but the current situation is not desirable or appropriate for the size of this monument. LP7 states the absence of a substantial disposition for development beside the existence of proposals for the utilization of the place, either for the creation of a theme park or for the abandoned proposal for the creation of an archaeological museum in the period 2000–2004 and specifically says: “As far as my assessment is concerned, there is no desire to utilize the archaeological site mainly due to money but also lack of ideas”. LP10 expresses his disappointment at the way the monument has been utilized and says characteristically: “It is a landmark of the area of global radiance that unfortunately we have forgotten to highlight!”

Additionally, LP17 states: “It is one of the most historic places in Greece and in world history. It has not been utilized as much as it should be. It needs interventions that will improve accessibility, hospitality and allow the organization of activities and events on a regular basis”. Finally, LP1 refers to the fact that the issue of promotion is not only a local matter but requires a wider perspective, even a national one.

Dark (Battlefield) Tourism Aspects (Resources Available, Current Offers, Possible Products)In this section, the listed answers focus on the question of resources availability concerning tourism development services at the point. LP10 refers to the existence of the available natural resources such as monument of Leonidas, Kolonos Hill, Information Center and in parallel points out the identification of a significant lack in the completeness of the information material. Several representatives note the availability of the financial resources of European and National funds. LP1 underlines the existence of guaranteed financial resources (e.g., Recovery Fund) but expressed worries about the phenomenon of bureaucratic delays. LP11 underlined the interest of the Greek State and analyzes the context of the anniversary year “Thermopyles—Salamina 2020” with cultural, scientific, humanitarian and educational actions. LP7 refers to the resources available by supporting that the regional programs had reduced the amount of available funds in comparison to the past, while other specific programs directed to support more central options and mentions the limited investments and interventions attempts in the archaeological site. LP7 refers:

“Till today, the interventions at least at the cultural level, e.g., in the archaeological area, have been zero. Consequently, if we exclude the municipal innovative museum with around 30,000 visits every year, we could not say that there was anything different in terms of investment”.

It is also noteworthy that 10 of the 23 participants stated that they do not know if there are resources available for the development of tourism services at the site of Thermopyles. Finally, regarding the “dark tourism” approach, an agency representative did not rule out the prospect of this version for this particular point, and LP18 specifically stated:

“If a spot may be probably promoted as a “dark tourism” category point, it can be excluded that there are supplementary “thematic products”, e.g., spa or cultural tourism that could be offered the promotion of a place or a historical/tourist resource depends on the market/country you are targeting and above all to which customers you would like to address”.

According to LP8 respresentative current tourism offers that exist in this period at the point concern the operation of the Thermopyles Historical Information Center which operates under the responsibility of the Municipality of Lamia. There is also a tour of the wider archaeological site as well as visits to buildings of the Ministry of Culture that host models with a thematic approach to the outcome of the battle and topography. LP22 underlines the fact that the Thermopylae Historical Information Center is located within the wider site of the Battle of Thermopylae and the exhibition spaces display the digital representation of the Battle of Thermopylae. Representative LP16 mentions that the building of the Center has a shape reminiscent of a spearhead which faces the side from which the Persians entered Thermopyles Pass. The Center functions auxiliary to the archaeological site by providing information to the visitor about the battle of Thermopylae and the topography of the area. In parallel, there is the organization of annual cultural events such as the event “Thermopylia” and a mountain race “Anopaia Atrapos”.

Tourist offices, according representative LP19, treat the site as an important stop-and visit point, where tourists simply pass through for a short time and take photos. LP19 characteristically mentions: “This fact is understandable due to the unorganized supply of the cultural and historical wealth of the place”. The representative LP7 estimates that in the last period the archaeological site is visited by about 30,000 visitors, a size that is assessed as a very small size. Access to the thermal baths is free and from time to time either a large number of campers gather there who stay on the site for 7 or 15 days or organized tours are offered by travel agencies in Athens. Also, the point of the thermal springs is approached by on-board visitors who are there to benefit from the legendary and priceless value of the thermal baths of Thermopylae.

The representative LP8 complements the fact that thermal tourism is also interesting in the adjacent thermal spring of Thermopylae, however the image of the area shows long-term abandonment. Representative LP1 highlights a different approach and emphasizes that the wider area of the point attracts people interested in mountain sports tourism (running, touring, cycling) mainly in periods when an easy access is ensured.

Also noteworthy is the fact that 12 of the 23 participants stated that they are not aware of any current tourism offers in relation to the site of Thermopylae. Finally, representative LP18 underlines that the “dark tourism” approach mainly concerns individual cases of expression of interest as the dominant interest focuses on the mass tourism of the region and in particular on the historical/cultural sector. However, it could work with the help of private initiative.

The representative LP5 states that for this specific point there are many possible proposals for the future related to the fields of history, culture, naturalism, gastronomy, thermalism. The LP10 representative suggests the upgrading of the offered services by the introduction of new technologies and through the search and evaluation of best practices from successful approaches. Especially states:

“We could search for good practices from successful experiences offered abroad, e.g., reenactment of specific moments (as in the case of Hiroshima Japan) at the time of the bomb’s detonation, naming, dioramas, information on costumes, thematic films, simulations, virtual reality, augmented reality, information on the battle preparation stage, experiential theme parks, seasonal schools, interactive events, marches on the paths and also the use of new metaverse-type technologies with virtual tours”.

In summary, the main suggestions of possible products or experiences offered are the following: “Tours of the natural landscape” “Tours on the mountain trail” “Specialized Spa tourism services” “Activities for history and nature lovers” “Thematic Experiential Parks, Planetary Village, Amphictyonia” “Innovative guest support services using equipment” “Books maps video comics”. “New productions (a) music (b) poetry (c) plays (d) literature” “Modernization and upgrading of the Center” “Improvement of parking area and access from the National Road” “Utilization of geothermal energy”. It is also noteworthy that 7 of the 23 participants stated that they do not know what the possible products or experiences related to tourism at the site of Thermopylae will be.

Finally, the representative LP18 underlines that with regard to dark tourism, no events have been established that can be linked to this category and no corresponding services offered are recorded.

Perceived Tourism Market Creation of the Site ThermopylesIn this section we comment on the results of the question whether the representatives of the local bodies consider that a tourist market has been created for the site of Thermopylae, it is noteworthy that 16 of the 23 participants stated that no tourism market has been created at the site, while only six representatives indicate that there is a small market with growth prospects. Representative LP11 points out that there is a lot of traffic to the site, which is expected to increase through the implementation of significant infrastructure and a network of trails.

The representative LP10 underlines as an important activity the existence of thermal tourism as well as beach tourism in the wider area, mentioning Kammena Vourla and Raches Fthiotida as typical examples. Also, an organized activity is said to constitute the “vagoneto” in a wider geographical area. Representatives LP11 and LP13 point out the fact the tourist activity in nearby destinations such as Kammena Vourla, Lamia, Ypati and Gorgopotamos. Representative LP18 introduces the dimension of student tourism and, on a smaller scale, the dimension of alternative tourism in the form of hiking trails. Representative LP1 reports that the area of Thermopyles attracts people for sports activities, such as mountain running, hiking, downhill cycling, as well as religious tourism to the Monastery of Damasta area. The importance of spa tourism is highlighted by two representatives (LP7 and LP8) according to which a great and lively interest from foreign tourists is recorded while the dynamics that could be developed from the better future utilization of spa springs are highlighted. Finally, in this section it appears that 10 of the 23 participants stated that they do not know if there are tourism activities offered for local development other than dark tourism.

Main Tourism Activities Except Dark (Battlefield) Tourism in Broader AreaThe main directions of local tourism development are the promotion of the wider region as an important pole of culture and tourism, recognizable at an international level as well as the utilization of the tripole Alamana-Thermopyles-Gorgopotamos and the dipole Delphi-Thermopyles. Representative LP13 summarizes the strategy of local tourism development based on thermal waters, Rally Acropolis, religious and sea tourism. Actions related to the scheduled creation of a cultural route of spa towns and religious tourism were also mentioned, as well as actions to highlight the path of Efialtis. The representative LP12 considers that the highlighting of the points of archaeological and historical interest in Thermopyles is specialized with actions undertaken in cooperation with the local authorities and they concern the restoration of the Wall of the Phokians, the unification of the archaeological site of Thermopyles and the accessibility improvement through individual walking paths and information areas. Additionally, it includes the technological and building upgrade of the Center, the improvement of the services provided to visitors, the enrichment of the exhibition content. Finally, one main issue is the utilization and promotion of the natural resource of the thermal springs of Thermopylae with the creation of a hydrotherapy center and a hotel. However, the majority of respondents (15 out of 23 participants) state that they do not know the direction and strategy of local tourism development. The representative LP7 reports:

“There is no complete plan. On the contrary, there are various fragmentary actions, but at some point, they will have to be combined with each other, as in some places even today they conflict with each other”.

Connection with Cultural and Heritage TourismIn this section, 15 of the 23 participants state that there is some kind of connection of the site with cultural and historical heritage tourism; however they express some concerns regarding the scope, design and result. The existence of the Thermopylae Historical Information Center proves the connection of the point as it presents in digital form both the historical events of the battle and various historical elements. Some representatives argue that the wider area of Fthiotida has an abundance of valuable but underutilized historical sites that could arouse the interest of tourists. LP11 argues that there is a broader connection of local historical sites such as Alamana with the sacrifice of Athanasios Diakos and the Gorgopotamos Bridge. However, despite the positive direction, there are reference points that raise issues of fragmentation, general planning, methodicality and efficiency. LP1 states that many people take the initiative to visit the site to see the battlefield, the statue of Leonidas, the digital representation and the area in general, but this action is a product of their own initiative and desire and not basis of some promotional or communication activity. LP19 points out that any connection of the point with historical and cultural heritage tourism is not the result of strategic planning process by the competent authorities of the state but comes from the partial implementation of the proposals of honorable elected officials and citizens as well as private business initiatives of excursion tours. Finally, 6 of the 23 participants state that they are not aware of any link between the site and cultural and historical heritage tourism, while characteristically LP7 points out that there is a risk that these sites will remain not only disconnected but also further discredited due to degradation and incomplete care of the wider area including the area of the thermal springs.

Actions of Local Authorities to Promote and Communicate the Point in Combination with Cultural ProductsIn this section, the majority of participants (13 out of 23) state that they do not know implemented actions in order to promote and communicate the point in combination with cultural products. LP3 states that promotional actions are minimal and without plan while LP4 refers that any movement is not targeted. LP23 adds that despite the existence of plans and studying reports, no significant action is undertaken to attract visitors and promote global visibility. However, opinions have also been recorded that claim that there is an attempt to connect by the local authorities. LP1 mentions that every September the “Thermopylia” festival is organized in the battlefield place and includes concerts, theatrical performances and other artistic events such as periodic exhibitions of photography and painting at the center. LP8 complements the positive aspects of the recent organization of a “forum” at the Information Center. LP11 underlines positively the organization of events and mentions characteristically:

“There are events organized by the Ministry of Culture, the local Ephorate of Antiquities through collaborations with the Region of Central Greece and the Municipality of Lamia. Events that have been established are the annual “Thermopylia” and the occasional organization of theatrical performances and sports competitions such as archery in 2018. Also, promotion events took place on the occasion of the celebration of the anniversary year Thermopylae—Salamis 2020”.

In the above actions, LP19 maintains some reservations regarding the regularity, effectiveness and efficiency of the actions. Finally, LP7 mentions that the local authorities, although they have planning, in reality, they have no authority over either the sources or the battlefield. LP7 characteristically states:

“At the same time, they do not have the financial capacity for such a venture, with the consequence that they remain either in appeals or pleas to the side of the competent government formations that have the ability but do not have the will to proceed with such a thing. Any actions planned for the next five years could be said to be opportunistic and isolated and do not meet the larger national debt towards Thermopylae”.

Establishment Prospects of Promotional OrganizationThe reaction of the representatives regarding the establishment of a promotional organization is very positive, as 18 of the 23 converge positively in this direction. LP1 refers:

“It would be a great advantage to have a legal entity under the supervision of the Municipality whose main job would be to promote Tourism and Culture in an area”.

LP2 supports positively the proposal and discusses the need to create a strategic plan with the cooperation of two local municipal authorities. Specifically, states: “I believe that it will be an important step because a Tourism Promotion Organization of Thermopyles with a specific and comprehensive strategic planning plan and with the cooperation of the two Municipalities (Lamia and Kamena Vourla) will help a lot in highlighting the area”. LP7 mentions that it is good to have a promotion organization but does not consider it necessary for the part of the battle of Thermopylae, as it is already known worldwide. Such a move could be helpful for the spa side of the spot as spa tourism has declined in recent years due to medical advances and the business focus on wellness should be redefined. LP8 adds that the promotional organization is a positive proposition and could cover beyond Thermopyles and the wider area of Fthiotida including the major areas of history (Thermopyles, Alamana, Gorgopotamos).

However, negative opinions have also been recorded for the operation of a promotion administrative agency, arguing that a private oriented organization would have better results and a more professional outfit. LP5 expresses concern about the project in question and exaggerates that by stating: ‘I disagree! The initiative should be private in order to have a strategy and result’. LP18 additionally states:

“I don’t think a special agency is needed, since the state (in all grades) has all the tools and legislation and money for promotion. I personally believe in the synergy of public and private agencies to create “thematic tourist routes” in order to achieve the appropriate tourism promotion”.

At a glance, it can be argued that the name Thermopyles is a globally recognized site with unique physical characteristics of the natural environment and historical incomparable elements from the battle of Thermopyles that guide the atmosphere of symbolism, ideals and values that make up the basic building blocks of modern Western civilization. The value of the historical name Thermopyles as a place of global influence gives unique prospects for the development of the wider region as a strategic geographical position and a rich history create conditions for the development of an important cultural, touristic and developmental pole of interest. The location is considered to be a magnet for both foreign and domestic visitors. It operates in addition to the Delphi-Thermopyles dipole and is located on the Athens-Meteora axis. The visitor can tour the site, the statue of Leonidas, the Hill of Colonos as well as visit the site of the thermal spring. Another point is the Thermopylae Historical Information Center of the Municipality of Lamia for information about the battle through interactive tables and video projection. The geographical area of the battle has been demarcated as an archaeological site and is subject to strict and specific legislative provisions. Most representatives consider that there is no market at the point despite the great interest from visitors. The existence of a small market is due to the fact of the anemic supply of specialized products and services. The current offers at the site concern the tour of the site, visit to the thermal springs and some periodical cultural and sports events in combination with student and educational interest, while the possible future offers could concern the introduction of new technologies and experiences for the visitor, the creation of tours and special events based on history and nature, new informational materials with a theme park and, in general, a qualitative upgrade.

In fact, except the operation of the Innovative Information Center, the installation of the King Leonidas monument and the cultural event ‘Thermopyleia’, there has not been a systematic effort to manage the brand of the place and highlight the local advantages for the benefit of residents, the local economy and development. Agents evaluate positively the potential establishment of specialized organization for the place development with red flags regarding operational issues.

In summary, the local representatives wish the highlight of the competitive advantages of the Thermopyles area through a coordinated effort of strategic planning of place branding with the participation of local economic stakeholders. However, this effort is undermined by the recorded long-term inactivity and the lack of corresponding soft intervention infrastructure based on the principles of sustainable development. Prospects are not positive regarding the achievement of visible and immediate results. However, the intention of future utilization is positively recorded. Finally, with regard to the approach of dark tourism and battlefield tourism, it is concluded that the conditions of dark tourism are not applied and the place marketing approach is based on the special characteristics of the location. Although there is a recorded belief in the future perspective of tourism development, this has not been specified with analytical characteristics and is at an early or initial stage without further indications of the development of dark tourism services.

Therefore, the aspects of sustainable development approach the mapping and the recording of the involvement degree of the local economic and social partners and the future sustainability prospects of the site. The economic, social and environmental impacts of visiting famous battlefield sites could be set on a comprehensive strategic plan in order to attract primary and first time visitors and support local businesses, employing and local taxes reception by increasing spending.

Suggestions, on how Thermopyles promote sustainable tourism strategies could be the development process of a strategic plan with the collaboration of the local partners (city council, local businesses, hotels, local cultural clubs, archeology, media etc.) beyond the implementation of a plan targeting to transform the site as a battlefield destination and the establishment of a local promotional organization. Also, it would help the marketing of local products and services related to the site (like wine, oil, sweets etc.). and the development of sustainable tourism strategies like the promotion of alternative tourism activities (e.g., sports events, cycling, trails, cultural events, educational historical events, ecofriendly events and battlefield reenactments). Due to the fact that the current project is limited on the side of local bodies further research focusing the opinions of tourists and visitors would specify the main motivational visiting factors and the generally perceived opinion of the site.

The dataset from the study is not available because they refer to personal interviews.

VK, TM designed the study. VK makes the theoretical part and research analysis. VK, TM wrote the paper. TM has the supervision of the study.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

Kalotas V, Metaxas T. Thermopyles: The Possibilities of a Global Brand Name Place in Forming a Strong Competitive Identity and Sustainable Development. J Sustain Res. 2024;6(2):e240019. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20240019

Copyright © 2024 Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions